Through the Eyes of a Hedge Fund Manager, Series #20

| 11 September 2024

Eriswell Market Insights

Diversification: No Forever Rules in Investing

BY MARK PAGE, MANAGING PARTNER

+44 (0) 1932 240 121

info@eriswell.com

© 2026 Eriswell Capital Management LLP

Nobel Prize winner Harry Markowitz once quipped that diversification is the only free lunch in investing.

His insight was simple: by diversifying across multiple asset classes, investors can achieve higher returns

without increasing risk.

A free lunch in other words. For which reason standard financial theory prescribes investing in a

diversified portfolio comprised of stocks, bonds, real estate, commodities, cars, wine, art, basically

everything.

But what precisely is the risk of this market portfolio compared to investing in individual asset classes

such as stocks and bonds?

An interesting paper was recently published by Ronald Doeswijk and Laurens Swinkels examining the

supposed benefits of investing in a so-called “Global Market Portfolio” (portfolio comprised all investable

assets around the world), and then examining the risk/reward characteristics of this portfolio over time.

Their conclusion that no obvious free lunch exists was unexpected by mainstream finance, although look

a bit deeper and things get murkier ...maybe it is available after all.

Either way, it’s worth understanding what’s going on and then taking an extra jump to consider

their findings in the context of today’s zero-r* world.

So, let’s take a look:

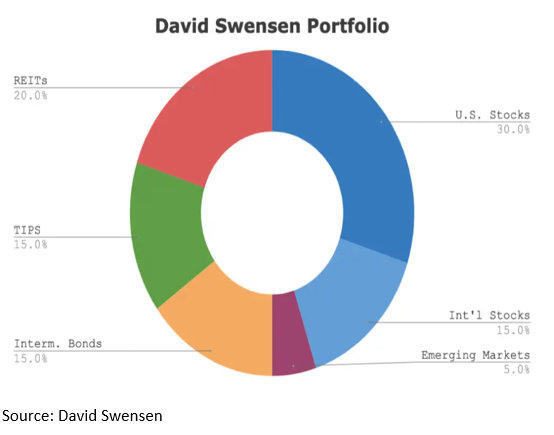

To begin, this paper defines its Global Market Portfolio as all assets owned by financial investors around

the world held in the ratios depicted in Fig 1. Note that the real estate category would be much larger if

it included residential real estate, farmland, and infrastructure, but much of this isn’t really tradeable on

public markets.

Fig 1: Composition of the global market portfolio

The most important thing to remember about zero-r* conditions is that there is no conventional

business cycle. We now live in a somewhat bizarre nonlinear world characterised by multiple semi-stable

equilibria, some of which persist for many years and some—like the ongoing inflationary spell— for only

a few.

Turning to the underperformance of value stocks today, notice how value also performed terribly in the

run-up to the 2000 Tech Bubble (Fig 1, red dotted line).

Now imagine if, at the end of 1999, you had finally thrown in the towel and bought tech.

Because in March 2000 tech stocks began to implode. Over the next decade to March 2010, the S&P 500

index delivered a negative return 0.7% per annum, dragged down by the S&P 500 Tech sector which

averaged a negative return of circa 8.0% per annum. Meanwhile the S&P 500 Energy sector delivered a

healthy gain of circa 9% per annum, and this 2000-2010 period also witnessed an outperformance of

small caps and emerging markets.

Turning points like that carry a risk for even the best institutions: Getting the flow of things kind of right,

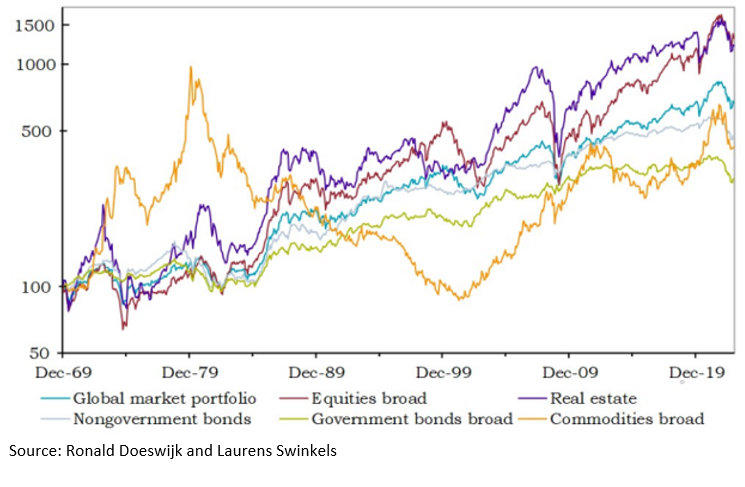

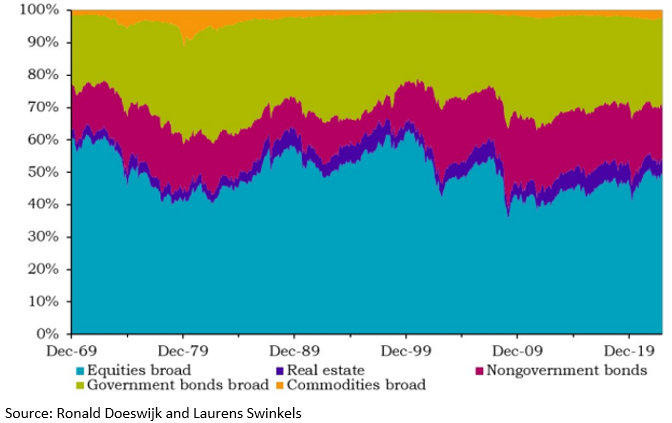

acting too early, then end up chasing hFig 2 depicts the cumulative returns achieved since 1970 by

investing in each individual asset class. Notice how closely aligned equities and real estate have been

over the longer term. Although bear in mind that stocks have massively outperformed bonds in 2023-24

after the dataset used in this study had terminated.

Optically the data suggests that for higher risk investors, stocks and commercial real estate are the best

assets to hold over the longer-term. Those with a lower propensity for risk might opt for a more

diversified Global Market Portfolio, and those with the lowest risk tolerance might choose a bond or

even a money market portfolio.

Exactly as conventional finance would prescribe.

Fig 2: Cumulative total returns for the Global Market Portfolio and its asset categories (USD, log y-axis)

Now here comes the fly in the ointment, according to Doeswijk and Swinkels:

“Despite its diversification across all globally invested assets, the global market portfolio does not have the

highest Sharpe ratio compared to the five asset categories over our 53-year sample period. Its Sharpe ratio is

only slightly higher than that of equities broad, but lower than that of nongovernment bonds.”

In plain English, at first glance diversification is a bit of a waste of time, there is no free lunch!

Note: For those unfamiliar with the concept, Sharpe ratios compare the returns achieved by an

investment against the inherent risk it carries; in other words, it tells us about the quality of returns. A

higher Sharpe ratio is considered better because it implies a higher investment return compared to the

amount of risk the investment carries. A lower Sharpe ratio vice versa.

Returning to the argument, the paper’s findings fly in the face of mainstream finance. Because it found

that a diversified portfolio delivers only a slightly higher Sharpe ratio compared to single asset

categories like stocks, with the only asset delivering a higher Sharpe ratio being government bonds. It

suggests there is no benefit to the quality of returns associated with a well-diversified portfolio.

Or simply, there is no free lunch!

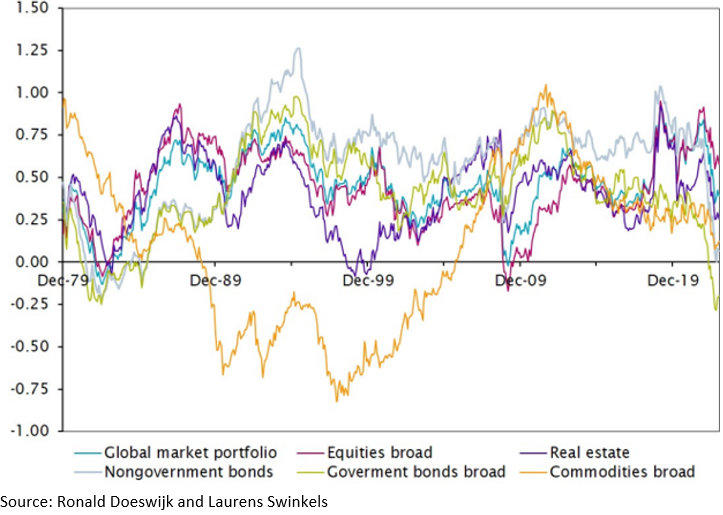

You can kind of see this optically in Fig 3, which illustrates the rolling Sharpe ratios of the different asset

classes. Notice how similar the Sharpe ratio for Global equities is to that of the Global market portfolio.

But now focus on the Sharpe ratio of the Government bonds broad asset class which has demonstrated

the best Sharpe ratio of all over time. This higher Shape ratio is one reason why pension portfolios

contain large allocations to bonds.

It is also why prior to 2022, many UK pension funds felt confident enough to chance their arm leveraging

Gilts via LDI strategies (Liability Driven Investing). Devising strategies around leveraging overpriced

bonds would prove disastrous.

Ever since year-end 2021, government bonds have performed terribly with those investing in such funds

losing up to 70% of their money depending on maturity. The collapse was so dramatic that on 28

September 2022 the Bank of England was forced to intervene to stabilise the UK Gilts market as a

consequence of which gilt yields (which move in the opposite way to price) fell by more than 10% on the

day of its intervention.

Returning to the Government bonds broad category (Fig 3), we can optically see what is going on.

Government bond Sharpe ratios bobbed along quite nicely in positive territory for almost half a century

since the 1970s inflation. Up until 2022, when it suddenly plummets below zero as collapsing bond

prices hammered investors.

So, RIP diversification? Not quite...

Fig 3: Sharpe ratios, rolling 120-month periods

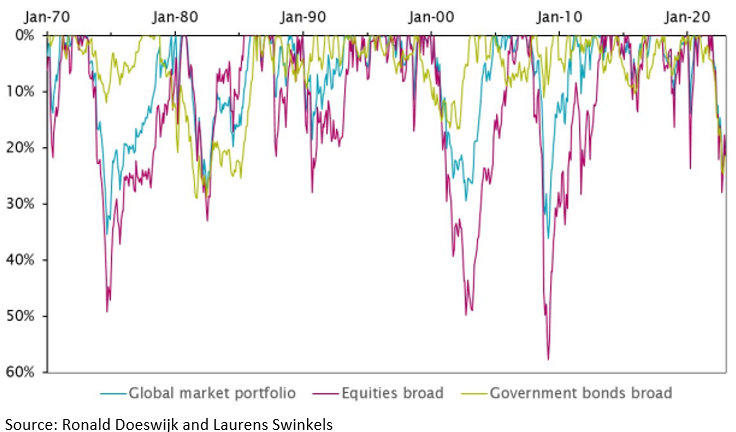

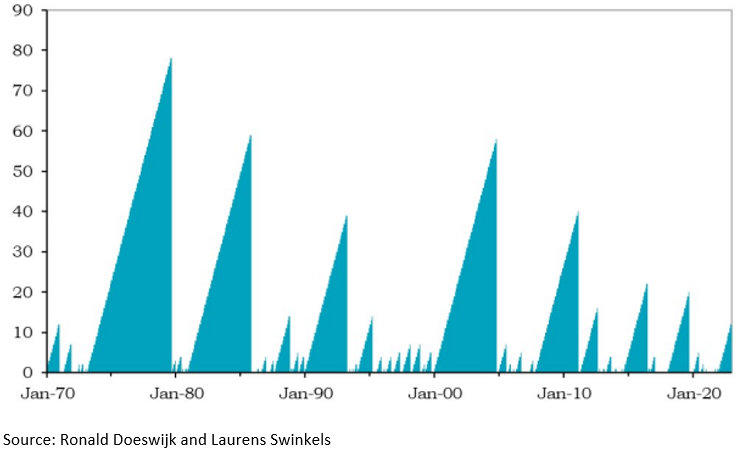

Another way to think about risk—instead of using mathematical measures like Sharpe ratios—is to

consider the magnitude of portfolio drawdowns when they occur (Fig 4) and how long it subsequently

takes for a portfolio to recover the incurred losses (Fig 5). Drawdowns being defined as the maximum

peak-to-trough decline suffered by a portfolio.

Doeswijk and Swinkels describe this in mathematical language:

“However, our newly collected monthly return data allows us to examine the time variation of the Sharpe ratios

of the five asset categories and the global market portfolio. The stability of the Sharpe ratio [for the Global

Market portfolio] over rolling decade samples is substantially greater than that of individual asset categories.

In other words, confidence in a positive Sharpe ratio for the global market portfolio over a decade is highest.”

“.....The risk literature suggests that investors care about the preservation of their capital. Monthly return data

allows us to estimate drawdown risk much more accurately. If we adjust the average returns by drawdowns

instead of volatility, the global market portfolio has the highest reward for risk, and the shortest maximum

drawdown period.”

In other words, it turns that after all, yes, diversification is a good idea for most investors concerned

about smoothing returns over the longer term.

Fig 4: Drawdowns of the global market portfolio, equities broad, and government bonds broad

Fig 5: Duration of drawdowns for the global market portfolio (number of months)

Pre-defined diversification can fail even the best investors

The conclusions to be drawn from this excellent paper will depend on individual investors, their

processes, attitudes to risk, etc. In terms of diversification there is no ‘forever rule’ which everyone can

safely follow in perpetuity.

Put another way, each investor must figure out for themselves how to deal with dynamic

conditions and even the best investors in the world risk catastrophic failure by formulating

‘forever rules’ and then sticking to them.

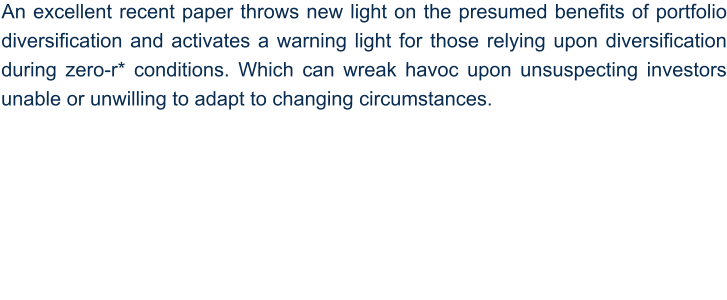

To illustrate this, the best example I can think of is the late David Swenson who ran Yale University’s

Endowment Fund, a man who is widely regarded as one of the greatest institutional investors in history.

Having had the pleasure of meeting him, I would say he was even better than his reputation.

But what I remember most about David was not so much his fantastic mind as his infectious open

mindedness, “Why do you say that?”, “Are you sure about this?”, “Does XYZ bother you?”

Investors as successful as Swenson always attract those who want to copy their portfolios and

outcomes.

To satiate this desire, Swenson designed his “Lazy Portfolio” (Fig 6) to help retail investors vaguely follow

Yale’s strategy over the longer term. This portfolio is well diversified and the weights of the respective

asset classes are rigorously kept in line with pre-defined weightings to maintain the required level of

diversification throughout time.

As it happens this portfolio has performed disastrously since 2020/21 and it has never delivered

the circa 3% outperformance delivered by Yale annually.

Why? Because it is comprised 20% of REITs (commercial real estate) which have performed poorly post

Covid, 15% US TIPS (index-linked bonds) which have performed terribly since 2022, and Intermediate US

Treasury Bonds, which have also performed poorly.

So that’s 50% of the portfolio which has performed badly over the past 2-years. No problem you

may say, that’s just the way diversification rolls.

The trouble is Swenson’s Lazy Portfolio is not even close to mimicking the returns the Yale Endowment

has achieved. Something which would be almost impossible for non-institutional investors, as Yale

follows a unique blend of strategies directed towards private markets, venture capital, alongside niche

and sometimes esoteric asset classes.

The point here being that people so often learn exactly the wrong lesson from great investors like

Swenson, by trying to copy their portfolios as opposed to understanding their insights, analyses, and

processes. alongside the culture Yale has built to help it become as successful it has.

Conclusion

For us, the takeout from the Doeswijk and Swinkels paper is that each investor must figure out for

themselves how to deal with dynamic conditions and that even the best investors in the world risk

catastrophic failure by formulating ‘forever rules’ and sticking to them.

Eriswell’s approach currently revolves around unravelling and understanding the intricacies of zero-r*

worlds, a unique and recent economic phenomenon still poorly understood by mainstream finance. This

has helped us to avoid and even profit from the collapse in sovereign bond prices and commercial real

estate prices since 2021 while benefitting from big rallies in many stocks.

Our same zero-r* insights and models are now flashing a sea of amber warning lights. Taken together

their message is to increase diversification while reducing allocations to the riskiest stocks and bonds.

In the context of Doeswijk and Swinkels, there remains a core logic in seeking to smooth returns and to

protect capital by diversifying over many different asset classes at times of high uncertainty and high

risk. Especially when one is unsure about accurately identifying precise pressure points and the catalysts

which might release them.

Moreover, at such times Eriswell has found that well diversified portfolio provides an excellent vantage

point for potentially violent market moves and a good position from which to intensify allocations as and

when opportunities arise.

Fig 6: David Swensen Portfolio

Mark Page