Through the Eyes of a Hedge Fund Manager, Series #21

| 11 October 2024

Eriswell Market Insights

Missing Massive Market Moves

BY MARK PAGE, MANAGING PARTNER

+44 (0) 1932 240 121

info@eriswell.com

© 2026 Eriswell Capital Management LLP

Convention has it that ‘value stocks’ outperform during recessions and bear markets, while ‘growth

stocks’ shine in bull markets and periods of economic expansion. The business cycle is therefore

key and this is important to know for professional asset managers and those seeking to time

markets.

Did this theory ever work? To some extent, yes, although the ability of investors to steal a march

on impending market moves through superior business cycle analysis is more fiction than fact.

Unsurprising, given that everyone knows about this supposed relationship.

What about today, haven’t value stocks been underperforming a long

time?

The most important thing to remember about zero-r* conditions is that there is no conventional

business cycle. We now live in a somewhat bizarre nonlinear world characterised by multiple semi-

stable equilibria, some of which persist for many years and some—like the ongoing inflationary

spell— for only a few.

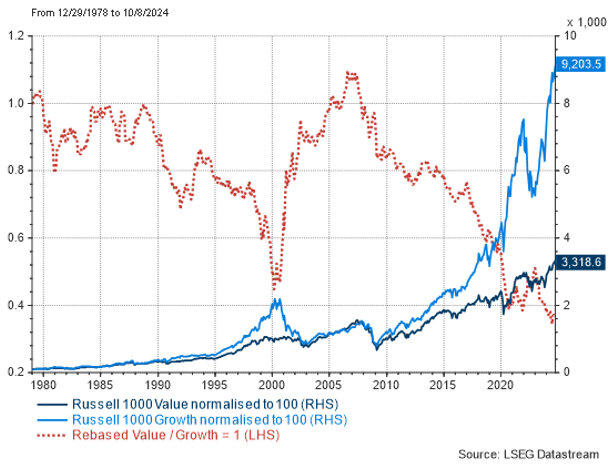

Turning to the underperformance of value stocks today, notice how value also performed terribly

in the run-up to the 2000 Tech Bubble (Fig 1, red dotted line).

Now imagine if, at the end of 1999, you had finally thrown in the towel and bought tech.

Because in March 2000 tech stocks began to implode. Over the next decade to March 2010, the

S&P 500 index delivered a negative return 0.7% per annum, dragged down by the S&P 500 Tech

sector which averaged a negative return of circa 8.0% per annum. Meanwhile the S&P 500 Energy

sector delivered a healthy gain of circa 9% per annum, and this 2000-2010 period also witnessed

an outperformance of small caps and emerging markets.

Turning points like that carry a risk for even the best institutions: Getting the flow of things kind of

right, acting too early, then end up chasing hot sectors and changing strategies at inopportune

times. Buying high and selling low.

Getting the big asset allocation decisions right is therefore paramount and one must remain ever

vigilant against becoming so obsessed with the timing that one blows the move.

Speaking of which, while simple charts like Fig 1 form no basis for informed decision making, the

outperformance of growth over value and the explosive rise of tech and narrative stocks, some to

the very edge of sensible valuations, must at the very least give pause for thought.

For the year 2000 represented one of those “all change” moments, the wrong side of which was

very painful. It is not inconceivable that, even if the big fiscal and monetary drivers of corporate

profits persist, that a similar secular pattern-shift happens in the not-too-distant future. We have

started to position for this but it is still early days.

Onwards to small caps...

Fig 1: Russell 1000 Value versus Growth, normalised, 45 years

Another well-known business cycle relationship: Small Caps

It’s ‘well known’ that the relative performance of smaller versus larger cap stocks tends to move in

line with lower grade credit spreads, i.e., the interest rate less creditworthy corporates pay over

benchmark levels.

The conventional explanation for this is that small caps tend to be more indebted, their financing

arrangements are generally more precarious, and they are hence disproportionately affected by

higher interest rates and widening credit spreads. Falling interest rates and narrowing credit

spreads should therefore benefit them more, and small caps should also be more influenced by

the credit and profit cycles.

No surprise therefore that small cap stocks have tended to outperform when credit spreads

tighten and when the corporate profit cycle improves, while large caps tend to outperform as

credit spreads widen and profits deteriorate.

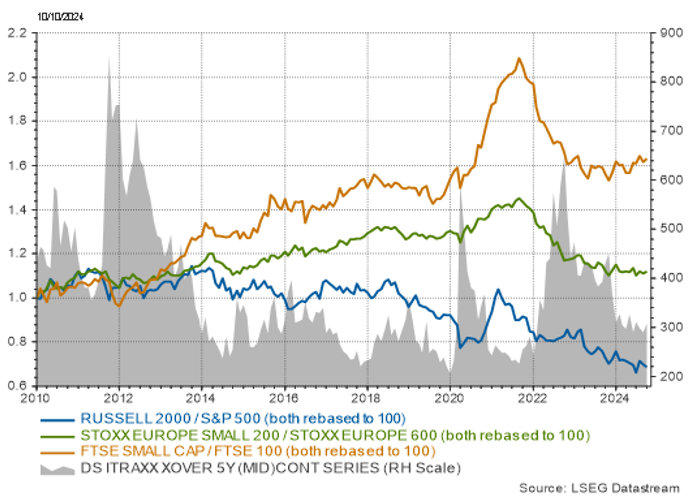

Yet something has been amiss recently: credit spreads have sharply narrowed since mid-2022,

meaning that small cap stocks should have outperformed strongly.

They have done exactly the opposite (Fig 2).

Does the post-2008 GFC (global financial crisis) offer an explanation?

In the US, the heart of the big-tech rally, small caps have been a disaster since 2008 (Fig 2). The

hope today is that if the Fed achieves a soft-landing, small caps could fly, although there have been

so many false dawns many investors have long given up on this.

In the EU post-2008, consistent with what conventional finance would suggest, small caps did

indeed steadily outperform larger caps up until 2022, after which most expected a further

explosive rally as credit spreads collapsed. Exactly the opposite happened, largely owing to the

difficulties posed by red-hot inflation, and over the past two years EU smaller caps have basically

given back their entire post-2008 gains.

The UK has been kindest to small caps although remember, as index sizes shrink, they can

become dominated and hence distorted by a few star performers.

Overall, smaller cap stocks haven’t really behaved as conventional finance says they should have,

especially in the US which is their largest market by far. Their post-2022 drop has severely

wrongfooted many investors pursuing traditional business-cycle metrics.

The most credible explanation for this as that these investors were blindside by the explosive rise

in inflation and the outsized problems this creates for smaller companies. Inflation is our next port

of call...

Fig 2: Small Caps Indices relative to Large Caps Indices and Itraxx Xover 5 years

‘Monetary Blitzkrieg‘ fuels skyrocketing inflation

Zero-r* conditions have persisted since 2007/08. From 2009, they repeatedly confounded

conventional wisdom as inflation and bond yields consistently fell against a backdrop of aggressive

central bank cuts and ballooning fiscal deficits.

Diametrically opposed to what mainstream economics predicted.

The insight back then was to recognise that the advent of zero-r* conditions had completely

changed the rules. And that exactly the opposite was about to happen, instead of monetary and

fiscal expansion fuelling inflation, they would simply slow a long slow descent into deflation.

As time went by, investors gradually adapted to this new low-yield/low-inflation world, even with

many bond investors ruing the fact that they maintained serially underweight bond exposures as

yields fell.

In the UK, actuaries running LDI pension funds were incredibly late to the game. Just as another

major turning point hoved into sight, they embarked upon a suicidal strategy. Leveraging paltry

bond returns in the hope of achieving a better yield.

A better example of buying high and selling low is hard to find, a mistake which would

subsequently require a Bank of England rescue mission for the UK Gilt market in October 2022.

The trouble was, just as everyone had adapted to this new world of perma-low inflation and

bond yields, central banks went too far.

Confident that inflation had disappeared from our systems for good, as a response to Covid, in

2020 central banks launched what Eriswell characterised as a rolling policy of ‘Monetary Blitzkrieg’.

The shock of this blitz powered what Eriswell termed ‘The everything rally’, where everything from

the price of bonds, stocks and residential real estate rallied skywards, alongside non-financial

assets like art, classic cars, fine wine, Bitcoin etc.

All this newfound wealth could at any point of course be exchanged for goods and services within

the economy. Which duly happened. Coupled with free state Covid payments, by 2020-21 this

artificial demand for goods and services was ramming hard up against the supply chains of goods

and services—especially services—which had been severely disrupted by the Covid pandemic.

Which quite predictably—at least to those including Eriswell in possession of newer

nonlinear zero-r* models—bounced western economies into a new semi-stable zero-r*

equilibrium, this time a fiery inflationary one.

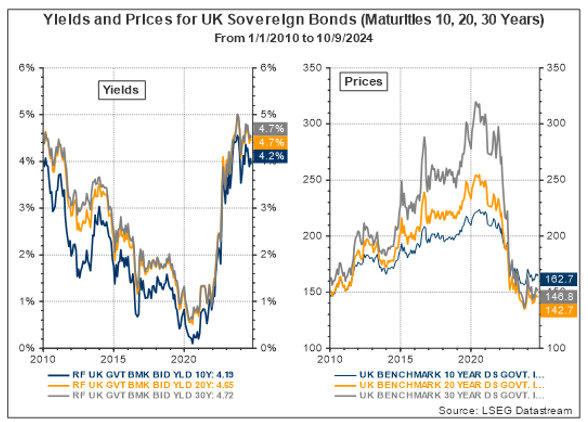

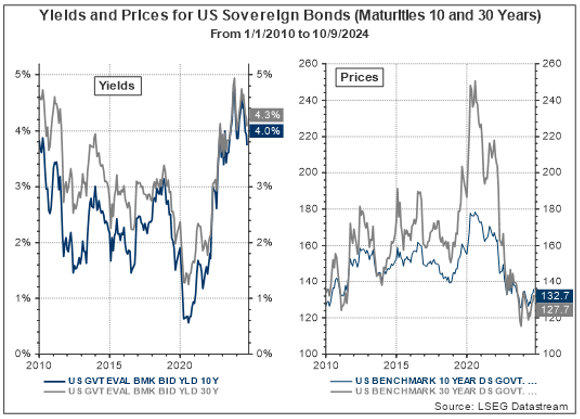

We all know the story, bond yields skyrocketed as bonds went on to suffer their worst selloff in 80

years (Figs 3 & 4).

Yet another blow in the face for conventional finance, including central banks which had

erroneously dismissed the rising inflationary pressures that they themselves had created through

de facto debt monetisation as “transient”.

Unfortunately, it was about to get even worse for conventional finance, in the largest asset

category of all, stocks...

Fig 3: The 2022/23 UK Bond collapse

Fig 4: The 2022/23 US Treasury Bond collapse

Stocks

From March 2022, as interest rates and inflation began to rise, stocks and especially longer-

duration stocks like the ‘Magnificent 7’ (Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, Meta, and

Tesla) began to fall sharply. In fact, 2022 would turn out to be a terrible year for them, largely as

mainstream finance predicted.

Yet a dramatic change in their fortunes was about to upset the applecart once more.

From the start of 2023 as inflation rose, corporate profits suddenly seemed immune to CPI rises.

In fact, they continued to rise even faster than their previous heady post-2009 trend (Fig 5), as

companies found themselves able to pass-on above inflation price increases to their customers

owing to the power of the artificial demand central banks had created. An environment which

would see corporate operating margins rise to all-time highs and fuel accusations of profiteering

and price collusion.

By now, the rate of corporate profit increases bore no comparison to the pre-2008, pre-zero-

r* world, where they had moved largely in step with NGDP and nominal wages (Fig 5).

Enter yet another curious but powerful curiosity of zero-r* environments: almost no matter

what governments do, fiscal stimuli almost entirely end up within corporate profits and within the

pockets of the wealthiest in society. Eriswell has spent a long time researching this, and the more

work we do, the more certain about this curiosity we grow.

However, blissfully unaware of this powerful driver, almost all of Wall Street, market strategists,

and economists, were blindsided by the sharp 2023 equity market rally. Especially with respect to

big tech, prompting Bloomberg to write a story in February of 2024 entitled: The Errors Tour: How

the Pros Bungled the End of Zero Interest Rates

Lastly, on to gold which also appears to have tossed aside the etiquettes of conventional finance...

Fig 5: Corporate Earnings growing faster than wages

Gold

We’ll keep this very brief as we’ve been through the arguments so recently, you’ll likely know the

entire musical by heart.

According to the experts, the yellow metal was destined to suffer big falls in 2023/24, as rising US

real rates amongst other perceived negative drivers made themselves felt.

Exactly the opposite happened as gold prices have gone on to hit one all-time high after another

(Fig 6).

Fig 6: Gold Bullion, London Bullion Market, USD per Troy Ounce (inc. Eriswell Recommendations)

Conclusion

Times are hard for central banks and mainstream finance, with many echoing Ophelia’s famous

Hamlet line, “Oh, woe is me, T' have seen what I have seen, see what I see!” She was trying to say

that while Hamlet was always noble, considering what he actually said and did, she wondered if he

had somehow become lost in his own self.

She may as well have been referring to zero-r* worlds and the woes of central banks and

mainstream professionals attempting to navigate them.

For zero-r* worlds are tricky, nonlinear, fiendishly complicated to mathematically model,

they can be disorientating, and one can easily get sucked into chasing hot sectors and

changing strategies at inopportune times. Buying high and selling low while either distracted,

unaware, or trying to finetune asset returns and portfolio volatility.

Put another way, getting the big asset allocation decisions right is almost always

paramount, and nothing should get in the way of this.

In terms of big asset allocation decisions today, we must bear in mind an ever-present feature of

zero-r* worlds. With conventional monetary policy waylaid for significant periods of time, central

banks require an alternative tool to encourage the inter-temporal forward shift in spending

required to jump-start stalled labour productivity growth.

QE, credit easing, and forward guidance were all designed to alter central banks standard

commitment to price stability into a more nuanced message: We commit to guaranteeing a future

where the path of nominal income re-equilibrates to the levels anticipated by investors and

borrowers when they undertook their nominal investments and debt”.

The central bank was in effect promising to turn a temporary blind eye, should the path of

nominal income growth temporarily display an uncomfortably high inflation component. Why, to

tactically fuel speculation as a tool to propel nominal economic growth.

The price to pay for this deliberate recklessness came in the form of the 2023/24 inflation

firestorm. It is easy to imagine that these implicitly reckless policies are gone for good and that is

certainly what almost everybody believes.

But they may be wrong again, we think that.

Looking forward:

The rising real value of debt will most definitely be a problem. This debt must be repaid, the

burden of which may well cause the price level to start falling again, forcing central banks to start

buying more bonds as the risk of another deflationary bust becomes clear.

And away we go again.

But will elevated deficits today definitively force an uptick in Gilt and Treasury yields, as

governments commit to but then find themselves politically unable to curtail elevated deficits?

That’s what all the experts think for sure, and the hope is governments pay heed.

But will stock markets react positively should governments manage to finally tame ballooning

fiscal deficits? Of course they will! At least, so say almost all the experts.

If there is any value in this note it is to drive home that when financial experts huddle for warmth

around a consensus view like this: Don’t feel confident, feel scared.

And in the case of stocks in today’s zero-r* world, we must remain ever-vigilant that if—contrary to

our expectations—fiscal deficits are indeed tamed, then corporate profits and stock prices may

lose the magic potion which has propelled them skywards.

This seemingly prudent eventuality may consequently herald a decade long period of stock

underperformance. Just as it did between 2000 and 2010. For clarity, we are not yet predicting this

but are watching carefully.

Have a great weekend,

Mark Page