Through the Eyes of a Hedge Fund Manager, Series #22

| 1 November 2024

Eriswell Market Insights

UK Autumn Budget: An Unmitigated Disaster

BY MARK PAGE, MANAGING PARTNER

+44 (0) 1932 240 121

info@eriswell.com

© 2026 Eriswell Capital Management LLP

Yesterday’s UK Budget represents a dangerous misadventure in the midst of the UK’s enduring stall

in labour productivity.

Before going further, of course the changes to Employer NI will be passed on in the form of lower

real wage growth. Of course, the other changes will underpin the ongoing exodus of the wealthy,

hardworking, and entrepreneurial people. Of course, it will generally increase the obstacles faced by

wealth-creators, savers, farmers, investors, pensioners, and UK businesses small and large.

But the problems are deeper than this. Two of them are worthy of close attention:

1. Misallocation of Capital

The dark ambiguities of multiple-semi-stable zero-r* worlds have finally turned dangerous for the

UK. Too many expert forecasts are infused with the naïve theology that the UK faces binary

outcomes: a soft or hard landing, growth or recession, inflation or deflation.

Reality is more complex than that.

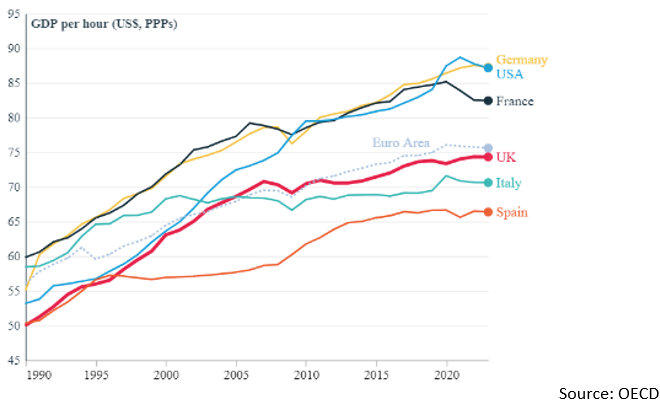

As ever, the UK’s future trajectory depends on what happens to stalled labour productivity growth

where we see few signs of an improvement (Fig 1, red line)

Fig 1: GDP per hour (USD, purchasing power parity converted)

The UK has performed exceptionally poorly against comparable economies in terms of labour

productivity growth since 2005, currently ranking well below France, Germany and the United States

and only slightly ahead of Italy and Spain. Between 2010 and 2023, annual average growth in UK

GDP per hour worked has flatlined around 0.5%.

This leaves the UK more vulnerable to economic shocks, especially to firms sitting at the bottom of

the productivity distribution. These are neither resilient nor adaptive, employ many low skilled

people, with many businesses barely surviving the economic pressures they are currently facing, let

alone potentially deeper problems up ahead.

Why has it come to this?

The ongoing collapse in UK and western labour productivity is primarily explained by a combination

of poor government policy choices since 2005, the aggressive monetary easing we have seen post-

2008, and unsustainable fiscal expansion.

This combination effectively halted the natural Darwinian destruction of poorly run unproductive

businesses, created speculative bubbles, and encouraged capital to flow into many dark corners it

should never have ventured.

Nominal-GDP growth is largely a function of government spending and commercial bank credit

creation for economic transactions. High real-GDP growth can only be achieved when this bank

credit creation ultimately flows in the direction of productive business investment: Opening new

markets, designing and implementing new innovative technologies, and funding an educational

system focussed on maths, science, and innovation.

No question, such an outcome requires a combination of a competitive tax economy, private

investment, innovation, top-flight third level education, and infrastructure investment which can be

delivered at least vaguely on time and within budget. That first point may be the most important.

Given that an enduring productivity stall lies at the heart of the UK’s zero-r* problems, policymakers

must remain ever vigilant against allowing fiscal spending to crowd out new productive private

investment in favour of building a bigger state; the weight of which is currently unbearable even for

an economy operating close to full employment.

Problems which will be only deepened by flinging taxpayer subsidies at weaker and zombie

companies while taxing more efficient companies and higher earners to pay for it all. And all

the while, encouraging more innovative, productive, and prudent companies to watch nervously

from the side-lines refusing to invest and hire staff more in such uncertain climes.

Round and round it goes, as this process gradually opens the door to capital and other scarce

resources straying down dark alleyways into spaces they should never have ventured. For this is the

colour of imperfect markets, imperfect information, and high fiscal spending; set within a UK

economy guided by the central hand of government and state agencies. This is not a political point

by the way, rather an observable economic phenomenon.

By contrast, the single most important proposition in economic theory, as described by Adam

Smith, is that free markets act as if guided by an ‘invisible hand’. Incentivised individuals acting in

their own self-interest do the best possible job of producing what is societally necessary. Not the

most perfect outcome, just the best available one. Extend Smith’s theory a little and we get

neoliberalism which kind of worked up until 2008.

However, the invisible hand has only ever worked in free markets characterised by prudent

investors and ongoing innovation. It ceases to exist in high-moral-hazard markets dominated by

government bodies, central banks, speculation, and productivity stagnation.

Problems which yesterday’s UK Budget will only further entrench. Can we put all this on a firmer

more mathematical footing?

Yes, but we need to be precise in how we go about this or we’ll be searching forever!

Fortunately, an insight Eriswell alongside some others happened to have back in 2013, pointed us in

the right direction. The strange behaviour of fiscal multipliers during periods of recession, and

especially during zero-r* conditions.

2. Curious Behaviour of Fiscal Multipliers in zero-r* conditions

The UK Budget will live or die on the battleground of whether all the announced new spending is

productive or not. In other words, what will fiscal multipliers turn out to be? That is the bang in

terms of future GDP growth for every £1 the government spends today.

Fiscal multipliers associated with government spending are generally small and negative during

expansions (i.e. normally). The new spending initially creates an immediate positive GDP effect as

the money is spent, but then that growth gain is lost and ultimately turns negative, owing to the

scarce resources effectively removed from the hands of productive companies.

However, fiscal multipliers can turn positive during recessions, very positive during zero-r*

episodes when interest rates fall to around zero. This is because at such points, the private

sector no longer possesses the ability to deploy the resources freed by government spending cuts.

In some countries (e.g. Spain in the mid-2010s) excess labour was slung into unemployment, in

others (e.g. UK) workers are forced into low paid jobs.

In other words, Wednesday’s UK Budget might have worked back in the mid-2010s when there was

a lot of free capacity in the UK economy and government debt could be raised cheaply at sub-1%

yields. Neither of these factors exist today, with low unemployment and a small output gap forcing

service sector inflation up, while sophisticated businesses struggle to hire highly qualified staff.

Can we represent this insight in more mathematical terms?

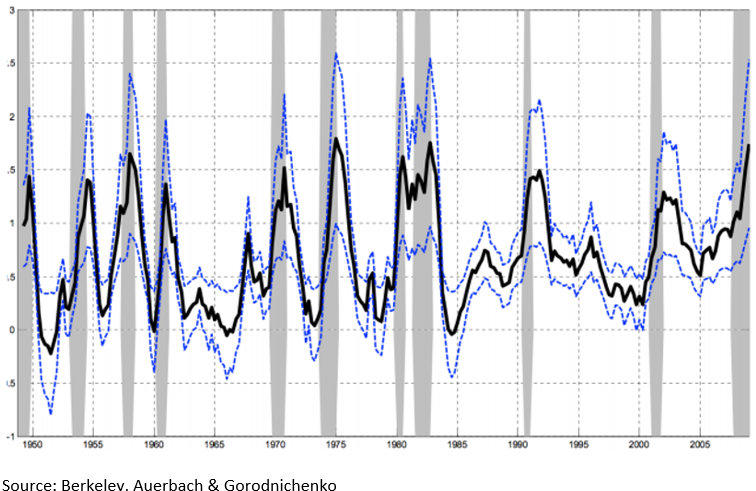

Absolutely, high ZLB (zero lower bound) fiscal multipliers are no longer a mere theoretical

prediction. In 2011, Berkeley University found the smoking gun in past OECD economic data. In

2012, the IMF half recognised this and effected a semi-policy U-turn on ZLB austerity. Fig 2 depicts

the key chart; please call for the papers, explanations, etc.

You would be forgiven for thinking that this fiscal multiplier stuff was something new. The fact that

we know about and understand them is relatively new, but research as far back as 2010

demonstrated that high multipliers during periods of recession are in fact as old as the hills. (Fig 3)

Fig 2 also illustrates the concept of hysteresis, basically the knock-on effects of government

spending today on GDP growth and real spending in future years. The high positive hysteresis

element, observable during recessionary periods, would build into a useful head of steam within

the economy which would benefit it in future years. And did benefit it between the years 2010 and

2020.

Now look what happens to fiscal multipliers during a period of expansion like today. Sure,

GDP growth is anaemic but that’s largely because of lethargic productivity growth and the fact that

spare capacity in the UK economy is currently short. (Fig 2: bottom lefthand pane)

In other words, fiscal spending today is likely to be GDP destructive even when spent on reasonably

sensible infrastructure investment. Meanwhile, increasing government spending to fund a bigger

state is likely to prove disastrous.

Fig 2: Many Fiscal Multipliers expand during recessions (green is zero line)

Fig 3: Unstable Fiscal multipliers in the US 1950-2009

Conclusion

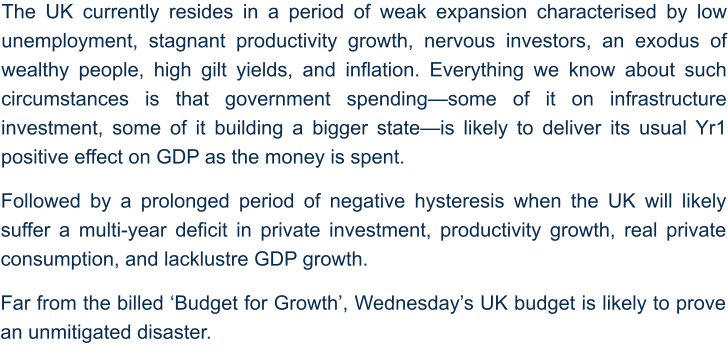

The UK currently resides in a period of weak expansion characterised by low unemployment,

stagnant productivity growth, nervous investors, an exodus of wealthy people, high gilt

yields, and inflation. Everything we know about such circumstances is that government

spending—some of it on infrastructure investment, some of it building a bigger state—is likely to

deliver its usual Yr1 positive effect on GDP as the money is spent.

Followed by a prolonged period of negative hysteresis when the UK will likely suffer a multi-year

deficit in private investment, productivity growth, real private consumption, and lacklustre GDP

growth.

Far from the billed ‘Budget for Growth’, Wednesday’s UK budget is likely to prove an

unmitigated disaster.

In the interests of political fairness, the last government also fluffed many opportunities: failing to

enact a high-multiplier/high-hysteresis investment fiscal spending programme in 2011-15 funded by

cheap government borrowing. It also made stupid mistakes like turning down Wellcome Trust’s

fantastic proposal to develop the 2012 London Olympic Park into a world-class centre for

innovation and technology.

The point is those times are long gone, today’s environment is very different, and policies that

would have worked in different times will not work today.

Finally, a quick word on all the OBR’s pious offerings on its forecast track for post-budget UK GDP

growth. These projections depend almost entirely on whether the UK can improve its productivity

malaise. The OBR has for many years been comedically wrong on its UK productivity forecasts (Fig

4), incorrectly predicting a return to the pre-2008 trend for almost a decade, after which it

attempted to cover its tracks in 2017, by blaming it all on Brexit.

In our opinion, the OBR does not understand zero-r* environments, its models do not even

recognise zero-r* as a thing. Its forecasts have consequently been wildly wrong for years, and we

expect them to remain wildly wrong for many years and tears to come.

So bad.

Have a great weekend,

Mark Page