People not principles drive our economies and financial markets: If people behave like Homer

Simpson, then we must investigate, understand, and forecast what Homer will do next. Not obsess

over how his perfectly rational alter-ego might behave in some idealised world.

As John Maynard Keynes’s put it:

"Successful investing is anticipating the anticipations of others."

We hope by the end of this series you will better understand:

i.

Why, since the 2008 Great Financial Crisis (GFC), economists and fund managers have

struggled to anticipate big stock, bond, and commodity price moves.

ii.

How to identify the investment risks and opportunities which lie up ahead.

There is, however, little point in offering solutions if we don’t first recognise the extent of the

problem. And this is not always easy in an industry whose participants spend fervently to protect

their reputations in the grand game of speculation: Which stocks are cheap? Which are expensive?

When is the next recession?

In a world where appearance is everything, PR campaigns can open an immense gulf between how

banks and asset managers are perceived, and what they deliver on the ground. It can prove very

expensive – it’s your money after all – to take this PR spin at face value.

So, has mainstream finance really done that badly?

Let’s start with US Treasuries, arguably the most important financial asset in the world.

i.

US Treasuries:

US Treasuries provide the axes around which mainstream finance revolves. When these axes

change, the orbits of the worlds revolving around them change too. Fail to foresee an axis shift and

you’ll likely miss the impending orbit changes. Consequently, investors use the Treasury yields as a

yardstick to gauge the expected returns from bonds, equities, emerging markets, and many other

assets.

Alongside most professional forecasters and economists, in May 20121 Goldman Sachs, predicted

that 30-year Treasury yields would rise from their then traded level of around 2.45% (Chart 1). In

July, Goldman Sachs’ US Treasury bond specialist Praveen Korapaty reiterated his forecast that

Treasury yields would rise, “frankly we think this is one of the places where markets have moved

substantially away from equilibrium".

As it turned out, Treasury yields would continue to plummet! By mid-August 30-year yields

had fallen to around 1.85%. And this was no one off, according to S&P Dow Jones, over 94% of

specialist US Treasury bond funds underperformed their benchmark in 2020 and are

underperforming again in 2021.

Extending the timescale, S&P Dow Jones tells us that, “….an incredible 99% of long bond funds failed

to clear the bar [their benchmark] over the past 10 years”.

Just 1% of active bond-funds beating their benchmark – Wow!

Part of this underperformance is simply a function of high fees in a low-yield world, but not all. For

example, economists and strategists who don’t run funds have also struggled.

Persistently low Treasury yields had important knock-on effects: politicians started to ramp-up

budget deficits with big fiscal expansions, corporates are taking on more debt, and private equity

houses are borrowing like crazy. In the household sector, mortgage debt is rising fast.

Why don’t credit markets reflect a ‘rational’ risk premium for such excess? Do rising deficits,

money supply, commodity prices, asset bubbles etc., truly not matter anymore? Curiously from the

get-go, Eriswell’s new zero-r*/behavioural models point to the existence of multiple semi-stable

equilibria in near-zero interest rate environments. As do similar modern models derived from

different thought lines – we’ll return to this.

The mistake, it seems, is to believe that these hitherto reliable leading indicators of inflation and

interest rates will influence yields this quarter, this year, or perhaps even in the next 5-10 years.

Does this mean that markets might come down with a bump when financial gravity is

restored? They might and we will return to this risk later in the series.

ii.

Surprise, surprise, stock markets are also behaving differently:

Once again, the professionals are struggling: According to the Chartered Institute for Financial

Analysis (CFA), since the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, US active managers have underperformed

the S&P 500 index in every single year, lagging by an average of 2.1% per annum.

At the end of 2020, Morningstar found that not one single US Large-Cap Growth Equity fund

had outperformed the S&P 500 over the past 10 years.

European long-only active managers have fared little better.

Once again, while high fees play a role in this underperformance, they are not the whole story.

As with bond markets, from 2013 onwards, stock markets would start dancing to a new tune with

two overriding new harmonies:

•

Companies could take on more debt at interest rates much lower than their credit rating might

suggest. Indeed, aggressive central bank action ensured this outcome.

•

The duration of corporate earnings increased. In other words, the value of expected earnings 5,

10, and even 30-years hence would swamp the value derived from earnings expected over the

next 5-years, the area where stock analysts spend most of their time.

Companies were quick to spot the opportunity. A combination of fallings yields, and a growing

professional credibility-vacuum – caused by persistent expert mistakes – freed companies to

connect directly with a new-breed of speculative investors: hedge funds, private equity, sovereign

wealth funds, mom-and-pop investors (driven out of bonds by falling yields), and the vast

Reddit/Robinhood army.

Regulatorily mandated corporate disclosures continue to feed the needs of traditional bottom-up

investors, while paying little attention to the information needs of these new-breed of investors.

They have consequently become much less relevant.

With the upshot that companies are increasingly free to court new-breed investors free from

regulatory restraint: telling stories and providing data in a manner of their choosing and which

supports their narrative.

These new stories can be extravagant and fun, often relying on non-financial metrics like subscriber

feedback, click trends, and customer interactions. Sometimes they are misleading (WeWork);

sometimes they are fraudulent (Wirecard).

One might call it a form of financial anarchy.

Now, one might not like this: but if stock markets are dancing a 1920s Foxtrot, it is never a good

look to be stepping out to Strauss’s Blue Danube. And it is certainly not profitable.

iii.

Deteriorating state of economics and central bank forecasting:

No surprise that economies are behaving differently today as households, businesses, and

governments all behave differently to the past. Even the central banks are struggling to keep up.

This has opened a tricky feedback loop back to financial markets which pay attention to every

central bank forecast, especially the Federal Reserve.

A 2018 paper, “Measuring the Accuracy of US Federal Reserve Forecasts”, found Alan Greenspan to be

consistently the most accurate forecaster amongst previous Fed Governors. More recent Fed

Governors such as Janet Yellen have performed relatively poorly leading to a tendency to make

fewer specific predictions.

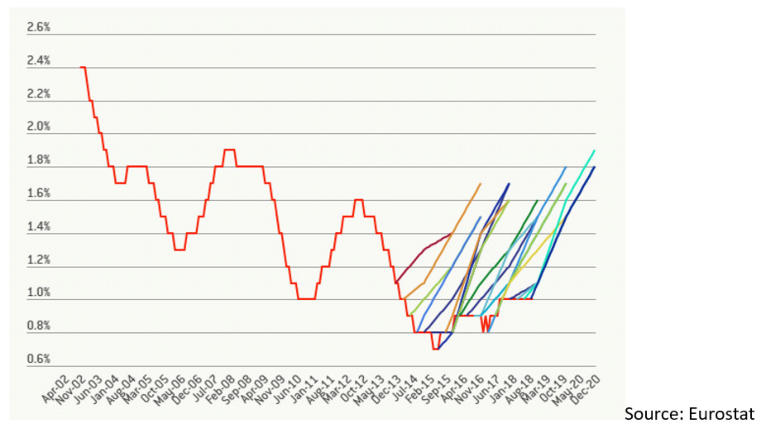

Turning to the Euroarea, the six years prior to the Covid-19 pandemic saw the ECB make a litany of

forecasting errors: core inflation remained broadly stable at 1% despite repeated predictions of an

increase (Chart 2), its persistent forecasts for a rebound in Euroarea labour productivity never

happened, while the Euroarea unemployment rate fell faster than the ECB predicted. The ECB’s

obstinate forecast of a bounce in Euroarea labour productivity has been confounded again and

again.

Moving to the United Kingdom, in November 2018, the Bank of England forecast that, in a single

year, the UK economy would contract by a massive 8%, and that UK house prices could fall 30%

under a disorderly Brexit scenario. That’s almost twice as bad as either the 2009 GFC or the 1930s

Depression.

An 8% GDP contraction in GDP is the kind of thing that follows a civil war, hyperinflation, or other

disaster, not a financial shock.

The Bank of England was widely derided for this mistake, and with even their baseline Brexit

forecast proving far too pessimistic, the BoE’s then Chief Economist, Andrew Haldane, admitted that

modern economics could not cope with “irrational behaviour” in the modern world, and that it must

adapt to regain the trust of the public and politicians.

And there’s the nub of it: the Homer Simpson like behavioural characteristics which

‘something’ has let out of the box, is increasingly confounding the predictions of the world’s

most sophisticated central banks.

Conclusion

‘Something’ powerful is forcing interest rates far below the levels which – by traditional yardsticks –

are consistent with their objective fundamentals. This something has radically altered the valuation

of many asset prices and mainstream finance doesn’t yet properly understand it.

If we don’t understand where this ‘something’ comes from, how it works, or where its headed, how

can we predict its journey into an uncertain future?

We can’t – as we have just seen.

The next note in this series will parachute back to the 1830s, a fascinating period where advancing

technology would heavily impact early-stage Western economies and the formation of our societies.

We were amazed at the parallels between what happened then and what is happening today;

perhaps you will too.

Chart 1: US bond yields, 10 and 30 years, 3 years

Chart 2: ECB projections for euro-area core inflation

(moving 12 months average rate of change)

Understanding Markets Today - Part 1

What Can’t Professionals See?

Economies and Capital Markets Series #6

| 3 September 2021

BY MARK PAGE, MANAGING PARTNER

Eriswell Market Insights

+44 (0) 1932 240 121

info@eriswell.com

© 2026 Eriswell Capital Management LLP