Humans are hardwired to dismiss facts that don’t fit their view of things. Psychologists call this

confirmation bias: the tendency of individuals to hold onto a certain set of beliefs about the

world by selectively seeking out information which confirms while ignoring information which

contradicts previously held beliefs.

Studies have shown that if you ask two groups of people (one which supports and one which

opposes capital punishment) to read two fictitious studies (one with evidence supporting and one

with evidence opposing capital punishment), both groups rate the study which confirmed their

pre-existing belief as superior and said it also enhanced their prior position – a finding which has

been replicated numerous times.

Because individuals are only ever looking for evidence which corroborates their prior viewpoint,

the same information or event can mean something entirely different to onlookers. (One only has

to attend a football match with a fan of the opposing team to find that out).

We hear a lot about confirmation bias and how it might explain excess volatility, momentum

trading, etc., but beyond definitions few sources delve deep enough into the psychology which

underpins this influential cognitive quirk of ours.

Why do we cling to our beliefs so strongly?

Your brain is always extracting information from the world. When nothing unexpected is

happening around us, the process is mostly automatic and one you don’t even realise. But when

something unexpected happens, our brain responds with an orienting reflex: our innate

response to an immediate change in the environment. It causes pupil dilation, galvanic skin

response, and heightened activity of the brain.

Let’s say you are sat at home watching television. Suddenly there is a loud crash upstairs when

you know you are home alone. The instant feeling you would have is because of the orienting

reflex, which physically prepares us to take action in case of potential danger.

This orienting reflex is extremely powerful and is activated by the smallest change in our

environment – something which puzzled neuroscientists in the 20th century because it

suggested, for the brain to detect when something new happened, it must also be keeping a

record of everything old that already had happened.

And they were right.

Why do models matter?

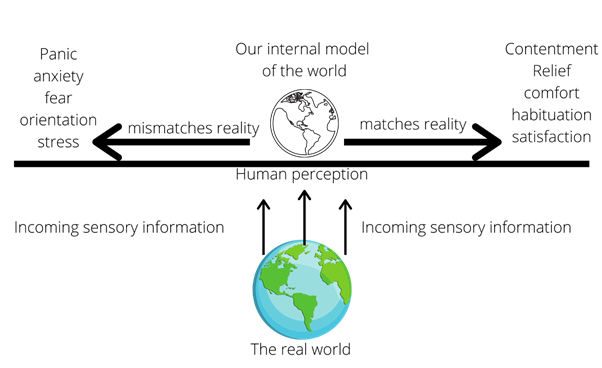

It turns out that one of the fancy things our brain – likely the cortex – does is generate internal

models which are partial representations of the world and our place within it. Then, as we act in

the world and extract information from it, our brain compares this newly acquired information to

the model we hold in our head. If they match, then our emotions stay regulated; if they contradict

one another, it means that there must be something unexpected in the environment, so the

orienting reflex is generated to prepare for action.

This capacity to generate complex models of the world and orient to change is a simple survival

mechanism and makes sense because, in our evolutionary history, the presence of something

unexpected would likely signify danger.

This is where it gets problematic for us though, given that we use the same brain circuits that

have existed for millions of years. Meaning that we still respond to changes in our environment –

however trivial – in the same way as our ancestors who had just found evidence of a nearby

grizzly bear.

Think of it likes this:

Our ancient ancestors didn’t have the option to cheat this diagram: if they only paid attention to

that which confirmed their model, they would have been eaten by a predator, wiped-out by a

neighbouring tribe, or starved to death with famine. For example, if you saw a bear lurking in the

woods, you wouldn’t have thought to scientifically confirm your pre-existing belief that bears are

dangerous – you would immediately run away!

Today, however, we have the luxury of choice. We can easily pretend not to have noticed that our

political opponent raises a valid point, that our favourite football player did in fact commit a foul,

or that we should have sold that stock six months ago.

The only choice we ever have

What this teaches us is that human beings are information-foragers – but somewhat selective

ones. We interact with our environment, extract data from it, and then build a partial

representation of that world in our heads from that data. Therefore, as we act in the world, we

have two basic options to choose between:

1) Assimilate the new information and use it to update our internal model of the world.

2) Ignore this information and maintain our existing model of the world.

The problem with the first option however is that it pushes you to the stressful left-hand side of

the diagram above. By assimilating new information, you are simultaneously acknowledging that

the information you previously held is no longer congruent with reality, which means that our

primitive brain systems put us into a state of preparatory action. Although this is by far the better

option in the long-term – your internal model will more closely approximate reality – it is stressful

in the short-term.

We want to cling to our existing models, systems, and explanations of the world because we don’t

want to experience the negative emotions that go along with acknowledging anomalous

information. As Warren Buffet once observed, “What the human being is best at doing is

interpreting all new information so that their prior conclusions remain intact.”

The relevance to confirmation bias is now self-evident: our emotions only stay regulated insofar

as our model of the world – that is, our existing set of beliefs – is correct. The temptation is

therefore to only pay attention to information which corroborates our beliefs because then we

don’t have to deal with the short-term stress. As John Maynard Keynes put it, "The difficulty lies

not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.”

Confirmation bias can also creep up on us over time with each individual rejection of relevant

new information being relatively small but, if you do this daily for a period of years, your internal

model becomes so divorced from reality that you have to engage in conscious deceit, denial, and

deception to continue to maintain it.

Confirmation bias opens up market investment opportunities in two

main ways

The first and in many ways the most straightforward is circumstances where the consequent

irrationality can be predicted ex ante. If everyone collectively takes the route of decision 2 –

ignore new information and maintain the stability of our existing models – then large groups of

investors will, over time, start clinging to outdated and erroneous economic models.

This process opens up investment opportunities for those few who are more open and willing to

note anomalous information and update their internal models of the world, even if it might be

stressful in the short term.

Or, as Keynes’s put it:

"Successful investing is anticipating the anticipations of others."

The second set of investment opportunities is more complex and was described by George Soros,

the iconic hedge fund manager. He argued in favour of the scientific method, which involves

making conjectures (hypotheses) from which we can derive logical consequences, and then

carrying out experiments to test their validity. When the hypothesis can’t explain the data, it must

be modified or ditched.

The beauty of the scientific method is that it is rigorous, gradual and deliberate, which by

definition has the opposite effect than those who only seek out information which confirms

previously held beliefs. By consistently generating new hypothesis and testing them against the

objective facts, we are forced to more ruthlessly abandon models which do not reflect reality – a

method which means we are far less likely to miss opportunities by holding onto existing

explanations and accepted wisdom.

It is equally important to remember that social systems (like the economy) differ from scientific

systems in a critical way. The philosopher Karl Popper for example argued that, whereas a

scientist cannot affect the physical system he is measuring, there is no singular reality within

social systems because our beliefs about the system alter its outcomes.

In other words: we are active participants in social systems and passive observers in scientific

systems. Human agency directly affects the outcomes of social systems but has no such power in

scientific systems.

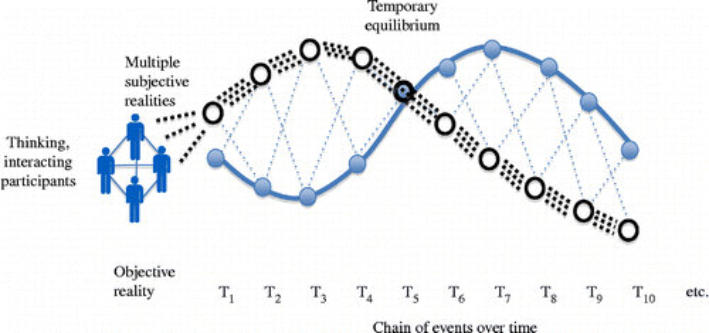

For example, in the Figure below the subjective realities of market participants (black dotted

lines) is only loosely related to the underlying objective reality (blue line).

For a time, the aggregate subjective realities of market participants actively affect the system

under observation: e.g., if everyone loves Bitcoin, or say Amazon stock, then these assets will rise

above the level suggested by their objective fundamentals. While human belief will affect stock

price, trouble comes at the point where optimism and greed is undermined by the objective

realities – at which point prices typically overreact on the downside.

Source: Soros

Avoiding Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is incredibly complex and grounded in our evolutionary history. If you manage

to find a fool proof way to combat this universal bias, then it’s Nobel Prize time for you!

That said, there are many techniques touted as helping to avoid confirmation bias:

1) Consider the alternative. Studies have found that thoroughly considering the opposite

viewpoint to the one you hold reduces confirmation bias.

2) Generate explanations for those alternatives. You should try your best to produce the

most logically-sound explanations for why the opposite viewpoint of yours might be correct.

3) Pick fault with your own viewpoint. Confirmation bias occurs because of our ability to

ignore evidence which contradicts our beliefs. Instead of propping up your beliefs via

rationalisation, try your best to think “in what ways might my initial reasoning be wrong?”

While no doubt sensible advice, does this kind of airport lounge self-help advice sound up to the

task of combatting a problem deeply ingrained within our psyches?

Of course not.

Our ability to selectively attend to information can be an incredibly destructive force when it

comes to how we invest, for it is the mechanism by which the individual can be divorced from

objective reality.

The ultimate point is that confirmation bias is so deeply engrained in our biology and

evolutionary history that there is no simple off switch – it is a pattern of our thinking which is

here to stay. The corollary to this is, if all human beings are saddled with this bias, a whole host of

investment opportunities appear.

To the extent that human beings are ‘predictably irrational’, investment fads, fashions, and

manias – which push asset prices far out of line with their underlying fundamentals – can be

exploited by those who acknowledge when the intrinsic biases of the human psyche might be at

play.

Part 2 of this article will pick up the story there.

Matthew S. Machin

MINDS AND MARKETS

The Truth About Confirmation Bias

Investors Should Know

Demystifying the relationship between psychology and finance

BY MATTHEW S. MACHIN

| Market Psychology Series #4

| 28 January 2021

Photo by Rvoji Iwata on Unsplash