Through the Eyes of a Hedge Fund Manager, Series #23

| 15 November 2024

Eriswell Market Insights

History Warns: Trouble Tomorrow, Possibly Crisis

BY MARK PAGE, MANAGING PARTNER

+44 (0) 1932 240 121

info@eriswell.com

© 2026 Eriswell Capital Management LLP

Angry and disillusioned, Americans have elected Donald Trump to lead their road to redemption.

Good intentions don’t suspend economic laws, however, and over the next four years voters will

learn whether Trump is the answer to their prayers or whether engrained problems prove more

intransigent than most believe.

We advise keeping two important factors in mind:

1.

To echo the words of Danish physicist, Nils Bohr, “Forecasting is difficult, especially

forecasting the future.” Never is this truer than during the zero-r* conditions of today.

2.

Markets aren’t perfect but they often surface problems; the rise in US and European longer-

dated yields is consistent with Eriswell’s prediction that fiscal deficits will prove impossible to tame

during ongoing zero-r* conditions.

Understanding the anger which simmers beneath the US and similar European outcomes is vital

to figuring the arc of things from here.

So, what does a Trump White House mean for markets in the US and beyond? The answer may

have more to do with the forces that put him there than the character of the man himself and a

quick trip back to the 19th century helps us understand why.

Zero-r* episodes, while rare, have historically been unhappy places characterised by technological

advances which fail to produce the new and better jobs required to mop up the cadre of workers

swept aside by advancing technology. This is the nature of an enduring stall in labour productivity

where, over time, workers grow mad with a system which produces no rising tide to float them

up. Over time, societies fray and governments fail.

Culminating in the simmering anger we see the US and Europe today. This is where the past can

provide us with many valuable insights.

Why place such an emphasis on history?

Because to understand the flow of things today we must understand the interrelationship

between economies, credit growth, markets, and people’s happiness throughout similar episodes

in history. To do this we must avoid falling into the trap of viewing historical events as an

inevitable sequence where outcomes could not have turned out differently. Rather we must try to

understand how those events appeared to people living through those times. Remembering that

our ancestors also had hopes, worries and expectations and that, just like today, they didn’t know

what the future held for them.

Hence reading history as it happened, as it unfolded day by day, reminds and cautions us as to

how uncertain things can be, and how differently events can unfold compared to the expectations

of those who lived at the time. For example, one of the ironies of the leadup to WWI is that none

of the then leaders wanted it to happen how and when it did. They never do.

Another example was the 2008 Global Financial Crisis where almost nobody foresaw that

individuals, companies, banks, and economies were all about to be plunged into a serious debt

crisis. And yet, an understanding of the circumstances of the Long Depression of 1873-96, the

Great Depression of the 1930s, and the Weimar Republic of 1918-33, enabled a small few to see

what was about to happen.

Similarly, the outbreak of an inflation firestorm in 2021-24 seemed inevitable to Eriswell, even

though we had never witnessed such an event in our lifetimes. The 1970s inflation was an entirely

different affair. It’s hard to see how any of these insights would have been possible without the

benefit of history; perhaps why central banks, economists, and mainstream investors have

performed so poorly of late.

The trick, it seems to us, is to understand the relevant history and to avoid at all costs trying to

judge it. How it ‘should have been’ or indeed ‘should be today’ have precisely no relevance here!

Let’s start our journey by parachuting back into early-1840s Berlin

We are now at the dawn of the first known labour productivity stall since the Industrial Revolution

commenced around 1750. You see despondent tailors pushing their creaky carts along the

streets, loaded with beautiful hand-tailored clothes they are selling at knockdown prices. You see

angry glassmakers, who had previously earned good money hanging around street corners, and

you can hear loud complaints from artisans in work whose wages are failing to keep pace with

rising costs.

The problem is the Industrial Revolution has recently brought new machines which can perform

the same tasks workers had, only for much less money. Over time the displaced tailors, piano

makers, glassmakers, steelmakers, and other skilled workers began to feel a new kinship with the

destitute and unskilled. Social tensions began to rise, not only in Germany but right across

Europe.

If you think about it, angry artisans have been at the forefront of every European social

revolution one can think of. It was they who stormed the Bastille in 1789, they who were the

force behind the July Revolution of 1830, and it was they who were about to finally revolt in 1848.

None of them had a clear idea of what they wanted, other than a better life and a desire to upend

the status quo.

Which was just about to happen. In France, the February Revolution of 1848 installed Napoleon III

as the first President of the “Second French Republic”. The unrest spread to Austria and Berlin

and before long peasant revolutions were sweeping the continent, going on to become known as

the Spring of Nations or People's Spring. The bourgeoisie-controlled administration in Frankfurt

was washed away and replaced on 1 May 1848 with the new Frankfurt Assembly, the first freely

elected parliament in an area of what is now Germany. It was a chaotic unstable affair and, by

late 1849, the Assembly had already descended into arguments and disarray, creating a vacuum

into which the illiberal German Princes and the Austrian Emperor stepped to regain control of the

region.

The parallels to the modern-day United States and Europe seem clear enough, as are the drivers

of the social anger we see today.

Onwards to The Long Depression (1873-96)

There were more European recessions in 1853, 1857, 1860, 1865 and 1869: notice how UK capex

and productivity swiftly returned to almost arrow-straight trajectories following these and almost

all other recessions (Fig 1). That is what drove the magic of increasing productivity.

Fig 1 is interesting in that we created it in 2011, the first time Eriswell twigged that—despite what

almost every conventional economist predicted—there would be no return to the previous 1.5-

2.5% trend growth in annual labour productivity which had reliably driven rising GDP output and

living standards for over 100 years. Recognising this problem opened the door for Eriswell’s new

zero-r* models which have since demonstrated an ability to identify major trend shifts to which

conventional economic and financial models remain blind.

While mathematically tricky, the underlying ideas and concepts aren’t so difficult if you spend the

time to break the relevant codes of history.

Moving on to Europe 1864.

Bismarck had mastered the skill of creating and then exploiting political and security vacuums for

his own ends. Having largely neutralised Russia politically after the Crimean War (1853-56) and

having defeated Denmark in the First Schleswig war (1848–1852), Bismarck created just such a

vacuum in the North German duchies of Schleswig and Holstein.

This time following a succession dispute concerning an heir acceptable to Bismarck after the

death of the Danish King Frederik VII. Bismarck initially indicated political indifference to the

selection of a new King but later, following the passing of the November Constitution of 1863

which tied the Duchy of Schleswig more closely to the Danish kingdom, Bismarck declared it to be

in violation of the previously agreed ‘London Protocol’ and he promptly declared war on Denmark.

Throughout this process, Bismarck became a master of first fomenting and then exploiting

popular fear, and in this way Bismarck would gradually piece modern Germany together. He

could have most certainly taught Trump a thing or two.

The point here, however, is that for those sufficiently informed at the time, the evolution of

Germany and other important historical and economic events gradually became visible some

time ahead of their occurrence.

Onwards to the exuberance of 1871.

German investors had chosen to target overseas investments throughout the unstable period

while Bismarck was at war, including being a significant force behind the post-US Civil War

railroad bonanza. In May 1871, following the Franco Prussian War, Bismarck finally defeated

France on which he promptly smacked a punitive war reparations bill representing some 23% of

French GDP.

That would settle France’s hash once and for all. Or so Bismarck thought.

To everyone’s surprise, including Bismarck’s, the French Treasury managed to quickly settle the

entire war reparations bill by selling government bonds yielding a hefty 5% to European

investors... with about a quarter of the new issues going to yield-hungry buyers in the newly

united Germany!

By 1871, with Germany now united and France free from its reparations’ penury, a wave of wild

optimism swept the continent. Bismarck might have been a bit miffed by France’s escape but

what nobody, not the Germans, French, nor anybody else recognised was that France’s escape

was a gift to the continent. For after WWI, Germany was subjected to even more viscous war

reparations than France, which went on to first create the Weimar Republic, then caused its

violent inflationary implosion, which in turn laid the ground for the arrival of a new populist.

Hitler.

Can you see the distinct parallels between these events and some of the credit and

political excesses we are witnessing today?

The 1867-73 period became known as the ‘Gründerzeit’ in Germany, characterised by a credit

fuelled construction boom and the arrival of some 145 new banks in Austria alone. This boom

would soon take on a darker tone with widespread participation in speculative investments, often

based on little more than the veneer of respectability offered by members of the nobility sitting

on the newly formed boards.

In May 1873, excess and leverage gave way to panic and deleveraging. The Vienna stock Exchange

collapsed, and the rest of Europe was soon engulfed. September 1873, “Black Thursday” saw

trouble arrive in the United States causing the binge in post-Civil War investment in US railroads

to suddenly grind to a halt. Before long, corporate earnings collapsed, stock markets began to

tumble, corporate bankruptcies skyrocketed, banks which had lent heavily to the speculative

sectors faced insolvency, unemployment shot up, and in 1873 alone US nominal wages fell by

some 23%.

By late 1873, the global economy had entered “The Long Depression”, one which would

persist for 23 years. An innocuous looking kink had appeared in the US and European

productivity trends. Unbeknownst to those living at that time, and to most people today, this was

the first major identifiable stall in labour productivity growth.

One which went on to derange the wheels of global commerce, slow investment, and injure

almost to death the mechanisms by which central banks control the economies under their

stewardship. Leaving the western world stuck in a liquidity trap not dissimilar to 2008-2021. UK

and US rates fell to near zero in the 1870s, credit aversion set in, and prices soon began to fall.

Bismarck imposes tariffs

Bismarck reacted by imposing harsh tariffs on all sorts of US goods (rye, cotton, iron ore, steel,

etc.) which were flooding the German markets. Basically, the carbon copy of what we see today.

Connections between Europe and the US gradually retreated to pre-US Civil War levels as the

German public gradually turned against liberal policies, against free trade, and against open

commerce.

Rising anger morphed into sweeping antisemitism in the belief that Jewish speculators were the

source of the trouble and tension would continue, culminating in the drums of war starting to

beat once more, this time in the lead-up to WWI.

Even to the greatest cynic, Bismarck’s and Trump’s instinctive attraction to tariffs have eerie

similarities.

And worth remembering that Eriswell’s understanding of zero-r* markets today would never have

been possible without first understanding what happened throughout this unhappy period.

Onwards to Japan 1996

Moving on from the Long Depression, more recessions in 1899, 1907, 1911, 1913, 1918, 1920,

1923, 1926, 1929–33 (The Great Depression), 1937, 1945, 1953, 1960, 1973, 1980, 1990. Notice

how many more recessions occurred back then and central banks today can be justifiably proud

of producing much better outcomes. That is as long as productivity growth keeps trundling along

in the background.

The next major productivity stall was curiously not the Great Depression which turned out to be a

more monetary affair. It would not occur until mid-1990s Japan.

Japan 1996

This would be Japan and the western world’s first glimpse in over a hundred years of a world of

dominated by multiple semi-stable equilibria, liquidity traps, and large fiscal stimuli. As during the

Long Depression of 1873-96, a combination of weak investment and falling productivity gradually

degraded Japan’s engines of GDP and real-wage growth.

Consequently, Japanese workers had less money to spend, corporate investment slowed to a

crawl and inflation steadily fell until it was bouncing off wage and other downward nominal

rigidities. Today, almost thirty years later, Japan is only barely escaping this unhappy state of

affairs.

It is absolutely vital to properly understand Japan’s woes in this period. For this was the first

time a productivity stall occurred within a modern developed economy, producing modern

statistical data, where the management of inflation was tasked to an independent central bank.

Forward to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis

Like Japan 1996, the US and Europe went on to suffer an enduring stall in labour productivity

growth around 2005/06.

Before long, what Eriswell terms the Wheel-of-Growth stopped turning under its own

steam.

In a normal economy, workers receive real pay increases commensurate to their improved

productivity, which when augmented with increased borrowings produce a natural tendency for

households and corporate to spend at a pace faster than the economy can produce. To restrain

this tendency, US and European long-dated nominal yields have since 1850 averaged between 3%

and 6% (equivalent to 2– 4% real rates).

In this space lives conventional monetary theory and a contented workforce.

When productivity growth stalled around 2005, monetary policy could do little more than help

facilitate the uptake of credit to plug the ensuing gap in aggregate demand. All the while hoping

that that labour productivity growth spontaneously recovered.

It didn’t, monetary policy and credit expansion continued apace. But instead of a repeat of the

Long Depression, central banks managed to contain the fallout in the form of a much shorter

crisis, albeit a serious one. Namely the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09.

The important point to recognise here is that central banks and governments have not solved the

underlying productivity problem, and our economies can therefore only grow under an ever-rising

burden of debt.

2008-21 was a different time to 2024

The election of Trump in 2016 and again in 2024 feels like a sequel to 1870s Germany with the

American electorate installing Donald Trump on a Bismarckian anti-trade and anti-immigration

ticket, alongside a Japanese-like commitment to endless fiscal stimulus.

Only this time in an environment which is inherently inflationary not deflationary. And that

matters big time.

Look a bit deeper and it’s not hard to see why Trump is so popular: between 2008 and 2021,

central bank policies had floated corporate profits and the holders of capital higher and higher.

While leaving what one might describe as the modern-day proletariat struggling to make ends

meet.

American workers feel they have not had a proper pay rise in a very long time, they have grown

fed up with what Trump calls the Davos World where elite businessmen rub shoulders with

politicians, film stars, and famous sportsmen.

Trump reasoned that those left outside in the cold could be incited to anger; he was right,

and no matter how much people may criticise him, Trump has played his hand beautifully.

One interpretation is that Trump and his administration instinctively understand zero-r* worlds

and possess the necessary zeal to finally grasp the labour productivity nettle, face down the

opposition, and implement radical new fiscal policies.

We don’t subscribe to this notion, preferring the description outlined by 19 century psychologist,

Gustav Le Bon:

“Nations have never lacked leaders, but all of the latter have by no means been animated by those

strong convictions proper to apostles. These leaders are often subtle rhetoricians, seeking only their

own personal interest, and endeavouring to persuade by flattering base instincts.

To the surprise of many, nothing terrible happened throughout the expansionary policies which

characterised Trump’s first presidency (2017-21). Their surprise rooted in a zero-r* curiosity that

defies conventional economics. Fiscal spending is not especially inflationary, rather it is generally

beneficial to economies sitting within the low inflationary semi-stable zero-r* equilibria which

characterised most of 2009-21.

Seen in this context, and setting aside some of his wilder notions, Trump’s fiscal policies were

pretty much the high-fiscal multiplier stuff (good spending) we and many others including Larry

Summers, Paul Krugman, etc, recommended for both the US and European economies in 2011-

18.

In the context of the US economy at the time, it was hard to see how Trump’s infrastructural and

education spending plans would be anything other than beneficial. And to the extent they were

enacted, they were largely positive.

Those days are long gone, and today’s inflationary environment is very very different.

Conclusion

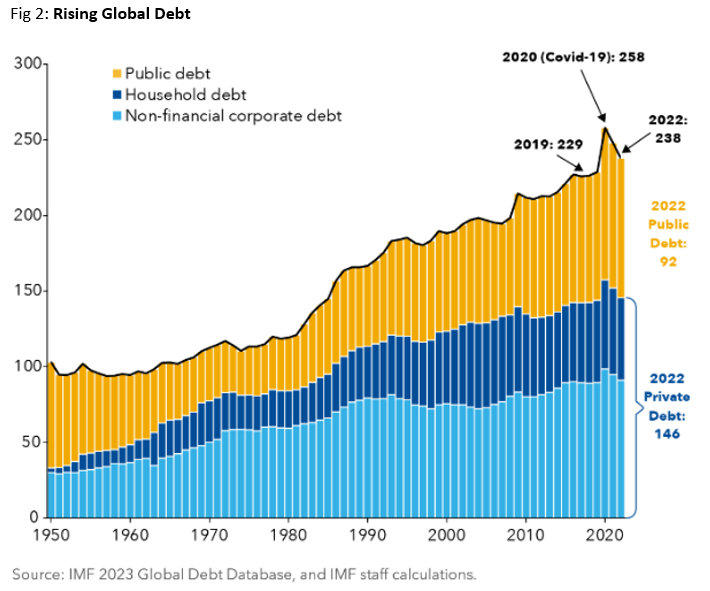

Today’s US economy is an entirely different animal to 2016 and so is the global economy: inflation

is running hot, output gaps are small, unemployment is low, and both private and public debt

continue to expand rapidly (Fig 2). Sovereign debt levels around the world are beginning to take a

toll on macroeconomic stability and squeezed government finances are starting to create

problems.

Prevailing debt dynamics are beginning to undermine growth prospects leaving many countries

exposed to the next economic downturn. Add to this mix the numerous structural challenges

required including demographic shifts, increased national security needs, and energy transition

and it’s hard not to be worried. Trump could conceivably hijack current anger to deliver

something positive against this backdrop.

Or he may lose control of the dark emotions he is whipping up with disastrous consequences.

Trump tells us he plans to increase tariffs (his favourite word he tells us), to implement sweeping

tax cuts, clamp down on immigration, weaken climate legislation, and loosen market regulation.

Policies he can likely enact much of given his new control of Congress.

Increasing tariffs to 60% on Chinese goods and 10%-20% for other imports would be problematic

for Europe and Asia alike. As in the 1870s, an escalation of protectionist measures eliciting

retaliatory action from the US’s trading partners would be negative for economic growth

prospects, for labour productivity, and for global security.

Aggressive immigration restrictions and forced deportations would tighten already tight US labour

markets, which coupled with the impact of tariffs and the associated costs of US and European

onshoring may well prove inflationary. It’s hard to be sure, but such uncertainty may well slow

the pace of Federal Reserve and other central bank rate cuts.

Now allow your mind to drift to what we saw when we parachuted back into early-1840s Berlin.

Think about what happened next.

And think about what might happen next today. The six-million-dollar question today is whether

Trump’s natural tendency to deregulate, to run big fiscal deficits, and to freely impose tariffs will

create chaos and crisis on the global stage.

The economist Ezra Solomon once quipped, “The only function of economic forecasting is to

make astrology look respectable”. Perhaps the best way to avoid this trap is to recognise that

uncertainty is exceptionally high today, and that 2, 3, 5, and 10-year forecasts have little serious

value right now.

Which is not in the least defeatist. Because if we can understand the history and understand how

zero-r* worlds work today, we stand a very good chance of seeing the inevitability of outcomes

others can’t see.

With sufficient time advantage to remain ahead of the game.

Have a great weekend,

Mark Page